Freezing Russia's Central Bank Reserves: Much Ado About Nothing?

Mattias Vermeiren

[March 2022]

Western countries have responded to the invasion of Ukraine with a plethora of sanctions that seek to completely isolate Russia from the western-dominated international financial and monetary system.[1] On February 26th, major Russian banks were cut off from the Brussels-based SWIFT international payments system, which provides messaging services that are needed to send money across borders. On the same day, jurisdictions issuing key internationally used currencies (especially the US and the EU but also the UK, Canada, Japan, Australia, and Switzerland) aimed to incapacitate the Central Bank of the Russian Federation’s (CBRF) use of its international reserves by effectively freezing more than half of the CBRF’s assets.

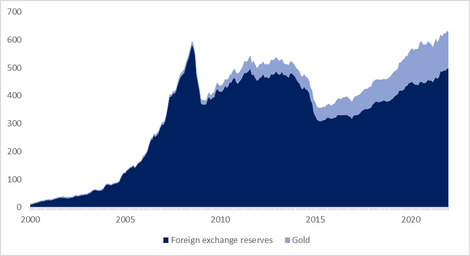

Especially the latter sanction is widely perceived as an unprecedented move that would debilitate Russia’s attempt to mitigate the impact of other financial sanctions like the exclusion of major Russian banks from SWIFT, which western powers already considered as a retaliation for Russia’s annexation of the Crimea back in 2014. Because president Putin and his fellow travellers probably expected a SWIFT-exclusion in response to the current invasion, they most likely hoped to rely on the CBRF’s reserves to mitigate the direct impact of these sanctions and continue to have access to the foreign currencies – especially US dollars and euros – that are necessary to engage in international trade and investment. After all, the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves over the last two decades by Russia and other emerging powers has been a central component of their growing “financial statecraft” aimed at strengthening their policy autonomy in the face of western-dominated international financial institutions and reducing their vulnerability against capital flight.[2] Russia alone had accrued more than US$630 billion in international reserves by January 2022, about 79 percent of which consisted of foreign exchange assets and 21 percent of gold (Figure 1). After its annexation of the Crimea in 2014, Russia stepped up its efforts to build a “war chest” of reserves, which peaked by the time of its 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 1. International reserves at the Central Bank of the Russian Federation[3]

Currency collapse?

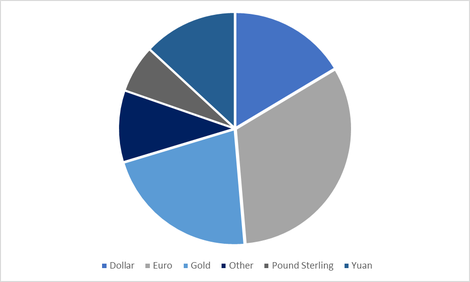

Foreign exchange reserves usually allow central banks to have immediate access to foreign currencies; they are a kind of deposit that can be deployed during a crisis to bailout domestic banks or defend the exchange rate against capital flight without having to resort to the IMF’s emergency loans and implement its harsh conditionality programs. In February 2022, almost 60 percent of the CBRF’s reserves were invested in western currency-denominated financial assets (Figure 2), enabling western powers to freeze these assets and undermine the capacity of the Putin regime to minimize the destabilizing effects of other financial sanctions on the Russian economy. One of the key economic objectives of the central bank sanctions is therefore to bring about a collapse of the exchange rate of the ruble, as one top official in the Biden administration openly acknowledged: “No country is sanctions-proof and Putin’s war chest of $630 billion in reserves only matters if he can use it to defend his currency value of the Russian ruble against major currencies, specifically by selling those reserves in exchange for buying the ruble.”[4] In the days following the announcement of the sanctions, the ruble plunged by almost 40 percent against the US dollar and the euro.

Figure 2. Composition of Russia’s central bank reserves in February 2022[5]

The underlying political objectives of the sanctions remain unclear, however. The most direct purpose is to limit the ability of Russia to finance the war against Ukraine by cutting of its access to foreign exchange markets and weakening the economic foundations of its geopolitical ambitions.[6] Western powers might additionally hope that the sanctions will eventually stoke social unrest and embolden ordinary Russians to openly contest “Putin’s war”: a collapsing currency would severely erode their purchasing power by making imports vastly more expensive and fuelling inflationary pressures in the Russian economy more generally. If so, it would reveal how western sanctions no longer only target Putin’s inner circle of siloviki and oligarchs but are explicitly designed to impoverish ordinary Russian citizens who bear no responsibility for the war. As Nicholas Mulder – author of the recently published book The Economic Weapon, an economic history of sanctions[7] – has forcefully argued, sanctions inflicting financial damage on entire populations are morally fraught: “any liberalism worth its name should support and defend individual dissent and resistance against oppressive and dictatorial governments, not punish those unfortunate enough to find themselves living under such regimes.”[8] Any hope to provoke popular revolt against the Putin regime would also be painstakingly naïve, as the sanctions could even boost societal support for the war by turning ordinary Russian citizens against western powers and making their economic fortunes increasingly reliant on protective actions of the government.[9] If regime change is the ultimate political goal, western powers could also prove dangerously reluctant to remove the sanctions as a condition for Putin to stop the invasion and withdraw his troops from Ukraine.

In the meanwhile, the Russian government immediately took swift actions to prevent the further fall of the ruble and bolster its exchange rate, facilitated by a major loophole in the sanctions regime: the exclusion of energy imports. Being the main channels for European payments for Russian oil and gas, Sberbank and Gazprombank were barred from the SWIFT sanctions.[10] Although the US and the UK eventually banned imports of Russian oil and gas, EU member states have been reluctant to go as far for fear of further escalating energy prices and triggering an economic recession. Combined with a sanctions-induced collapse of imports, continued exports of oil and gas at elevated prices can be expected to boost Russia’s current account surplus and sustain its access to new inflows of foreign exchange. At the same time, the Putin regime responded to the sanctions by introducing exchange controls that ban Russians from transferring foreign currency abroad and force Russian exporters to sell 80 percent of their foreign currency revenue for rubles.[11] Together with the sustained energy exports and related influx of foreign currencies, these exchange controls have managed to partly recover the exchange rate of the ruble, which re-appreciated by more than 30 percent against the US dollar and the euro in the last three weeks of March. Putin’s decision on March 23rd to demand “unfriendly countries” to pay for Russian gas in rubles was therefore largely symbolic, as it merely would force European importers rather than Russian exporters to sell euros for rubles.

The ruble’s partial recovery certainly does not imply that the Russian economy will remain unscathed from the central banks sanctions: to defend the ruble, the CBRF also had to raise its main interest rate from 9.5 percent to 20 percent in ways that will (together with other economic sanctions) contribute to a severe recession and put severe hardship on Russian citizens (as well as on migrant workers in Russia and people relying on their remittances). But the energy loophole does suggest that the central mechanism of these sanctions – i.e., a causing a complete collapse of the ruble – has failed to bite.

Global financial fragmentation?

What about the long-term consequences of the central bank sanctions? Freezing the CBRF’s foreign exchange reserves seems to have eroded the “moneyness” of these reserves, the perceived safety of which has always been based on their alleged liquidity and ease at which they can be converted into hard currencies.[12] By “weaponizing” foreign exchange reserves, western powers could give non-western central banks an incentive to diversify their reserves away from assets denominated in western currencies: it could, as some observes like Barry Eichengreen have argued, accelerate the stealth erosion of the US dollar as the dominant reserve currency.[13] After all, Russia responded to the 2014 sanctions by further de-dollarizing its reserves, shifting to gold and especially euros instead.[14] The central banks sanctions could now even alter the political calculations of China – which currently holds more than US$ 3.3 trillion in international reserves – and push it to ditch the US dollar as its main reserve asset.

This raises the question about alternatives. The perceived moneyness of foreign exchange reserves is the key reason why gold cannot be seen as a plausible substitute: it is difficult if not impossible to swiftly sell huge volumes of gold for US dollars or other international currencies without incurring massive losses on these sales; even though the CBRF diversified its international reserves toward gold, its gold reserves – amounting to more than US$130 billion in February 2022 – will most likely remain largely idle over the next few months. The unique deepness and liquidity of US markets for debt securities – especially the market for US Treasuries – is the principal foundation of the dollar’s dominance as the world’s reserve currency: central banks can easily liquidate these debt securities and/or use these assets as collateral in repo funding markets to borrow US dollars at minimum transaction costs. Other currencies are not backed by comparable markets for debt securities and lack a similar level of liquidity. The international role of the euro has been constrained by the fragmentation of the Eurozone’s (sovereign) bond markets and its restrictive macroeconomic policy regime, which curtails the supply of safe and liquid debt securities to the rest of the world by privileging the interests of the export-oriented growth models of the northern member states.[15] The cross-border trade of yuan-denominated assets, in turn, has been impeded by persistent capital controls, which play a crucial role in China’s investment-led growth model by enabling the Chinese government to channel cheap credit to its state-owned enterprises.[16]

While remaining the world’s dominant reserve currency, it is perfectly conceivable that the western sanction regime will somewhat reduce the share of the US dollar in global foreign exchange reserves by inducing possible contender states to look for alternatives. The sanctions will also further encourage emerging powers to settle their bilateral trade in their own currencies instead of the greenback. Both Russia and China have already set up their own financial messages systems to reduce their reliance on SWIFT and US financial institutions to settle their trade. Even so, it is essential to remember that the dominance of the US dollar goes way beyond its role as the global reserve and trade settlement currency: the most important source of the global hegemony of the US dollar – and the structural power it confers upon the United States – is that it is by far the most favoured investment and borrowing currency for private actors in global finance. A recent McKinsey report estimated that the total value of financial assets and liabilities in 2020 amounted to more than US$1,000 trillion (12-times global GDP).[17] Only the onshore and offshore US dollar markets are sufficiently large to absorb the global need for private financial and non-financial firms to raise funding and accumulate liquid financial wealth. The willingness of the US Treasury and Federal Reserve to backstop even offshore US dollar-denominated money created outside the US financial system in response to the global financial crisis of 2008 consolidated the position of US dollar as the world’s dominant store of value.[18]

Wealthy elites in non-western countries might infer from the current sanctions that “they can easily fall victim to geopolitics” – as Branko Milanovic has argued – pushing them to “find new havens for their investments … probably in Asia.”[19] Nevertheless, stashing their financial wealth into US dollars in non-western financial centres can still expose them to US secondary sanctions that punish these centres from doing business with targeted elites. The only other option is to invest in real estate instead of financial assets, pushing up housing prices in non-western jurisdictions. But should the United States and other western powers really care about this “risk”? Rather than fragmenting the global financial system around competing geopolitical blocs, the flight of their money could ease some pressure on skyrocketing real estate prices in several of the West’s overly expensive global cities and ought to be welcomed for precisely this reason.

Endnotes

[1] For a complete overview and timeline of the imposed financial and economic sanctions, see Chad P. Bown, “Russia's war on Ukraine: A sanctions timeline,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, last modified March 29, 2022, https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/russias-war-ukraine-sanctions-timeline/

[2] Cynthia Roberts, Leslie Armijo and Saori Katada, The BRICS and Collective Financial Statecraft (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

[3] Central Bank of the Russian Federation

[4] Anonymously quoted in Amanda Macias and Thomas Franck “Biden administration expands sanctions against Russia, cutting off U.S. transactions with central bank,” CNBC.com, February 28, 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/28/biden-administration-expands-russia-sanctions-cuts-off-us-transactions-with-central-bank.html.

[5] Source: Central Bank of the Russian Federation

[6] Carla Norrlöf “The New Economic Containment: Russian Sanctions Signal Commitment to International Order,” Foreign Affairs, March 18, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-03-18/new-economic-containment.

[7] Nicholas Mulder,The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War (Yale: Yale University Press, 2022).

[8] Interview of Nicholas Mulder by Anny Lowry, “Can Sanctions Stop Russia?” The Atlantic, March 10, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/03/russia-sanctions-economic-policy-effects/627009/.

[9] Lee Jones, “Sanctions won’t save Ukraine,” UnHerd, February 28, 2022, https://unherd.com/2022/02/sanctions-wont-save-ukraine/.

See also Lee Jones’ book on sanctions: Lee Jones Societies Under Siege Exploring How International Economic Sanctions (Do Not) Work (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[10] Philip Blenkinsop, “EU bars 7 Russian banks from SWIFT, but spares those in energy,” Reuters, March 3, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/eu-excludes-seven-russian-banks-swift-official-journal-2022-03-02/.

[11] Katie Martin, Tommy Stubbington, Philip Stafford and Hudson Locket, “Russia doubles interest rates after sanctions send rouble plunging,” Financial Times, February 28, 2022 https://www.ft.com/content/f7148532-36cd-4683-8f1b-ea79428488c4.

[12] Jon Sindreu, “If Russian Currency Reserves Aren’t Really Money, the World Is in for a Shock,” Wall Street Journal, March 3, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/if-currency-reserves-arent-really-money-the-world-is-in-for-a-shock-11646311306.

[13] Barry Eichengreen, “Ukraine war accelerates the stealth erosion of dollar dominance,” Financial Times, March 28, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/5f13270f-9293-42f9-a4f0-13290109ea02.

[14] Daniel McDowell “Financial sanctions and political risk in the international currency system”, Review of International Political Economy 28, no. 3 (2021): 635-661.

[15] Mattias Vermeiren “Meeting the world’s demand for safe assets? Macroeconomic policy and the international status of the euro after the crisis”, European Journal of International Relations 25, no. 1 (2019): 30-60.

[16] Miguel Otero-Iglesias and Mattias Vermeiren “China’s state-permeated market economy and its constraints to the internationalization of the renminbi”, International Politics 52 (2015): 684.

[17] McKinsey Global Institute The rise and rise of the global balance sheet: How productively are we using our wealth? November 15, 2021, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/the-rise-and-rise-of-the-global-balance-sheet-how-productively-are-we-using-our-wealth.

[18] Steffen Murau, Joe Rini and Armin Haas “The evolution of the Offshore US-Dollar System: Past, present and four possible futures,” Journal of Institutional Economics 16, no 6 (2020): 767-783.

[19] Branko Milanovic “The End of the End of History: What have we Learned So Far?”, Global Policy, March 7, 2022, https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/07/03/2022/end-end-history-what-have-we-learned-so-far.