The Energy Crisis and Global Climate Goals: Popping Empty Promises?

By Hermine Van Coppenolle

[January 2023]

Hermine Van Coppenolle is a doctoral researcher with the Ghent Institute for International and European Studies at Ghent University. Her research centres around the drivers of global climate ambition and global climate governance, focusing on the 2015 Paris Agreement.

In a world where climate change is felt more and more deeply each year, the need for climate action becomes increasingly pressing. Observers are noting an increasingly tight geopolitical climate for environmental action caused by the war in Ukraine and the resulting food and energy crises.[1] Are countries maintaining their trajectory towards limiting global warming, or are their climate plans popping under the pressure of the energy crisis?

This paper first zooms into the status quo, detailing why looking at climate pledges is becoming increasingly important and where climate action has been coming short. Next, this paper looks at how the energy crisis has been dealt with, and reflects on what this means for climate action in the medium and long term.

The importance of climate pledges

With the adoption of the Paris Agreement, there has been an increased focus on formulating climate plans and climate goals. This is because the Paris Agreement introduces an overall climate target instead of setting specific emission reduction targets in stone for each involved country. Three targets, in fact, are central to the Paris Agreement: limiting global warming to 2°C, aiming for 1.5°C and reaching net zero emissions by the second half of this century. In order to reach these targets, countries formulate their own climate plans, or ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’ (NDCs). These NDCs play a central role to the Paris regime, as it tries to foster climate action through repeated cycles of reformulating these plans and raising ambition.[2]

The Agreement has created an iterative process where countries’ main obligations are to formulate NDCs, communicate progress reports and emissions data, and systematically raise ambition. This process aims to close the so-called ‘ambition gap’, or the space between policy plans and the goals set out by the Paris Agreement itself. This ambition gap, though central to the whole debate, is only one of the challenges that countries face on the way to effective climate action.

The gaps to bridge

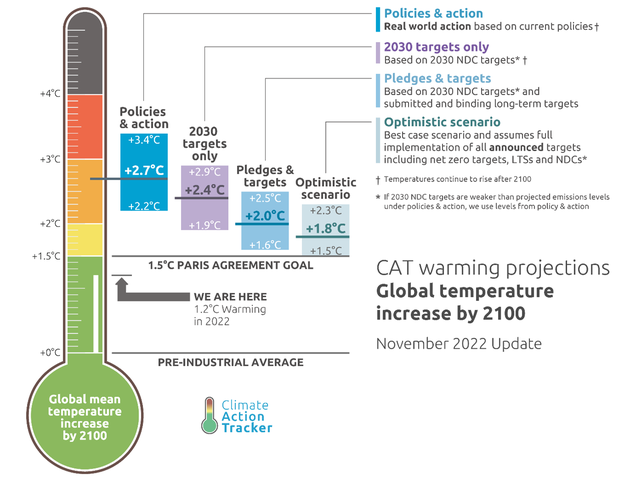

When it comes to global climate governance, there is both the ambition gap and the implementation gap that needs to be dealt with. Both of these are visualised in figure 1. On the one hand, it shows the gap between the overall goals of limiting global warming to 1.5° and 2°, and the warming projections of policies and actions, targets, and pledges. On the other, it shows the gap between the actual policy and the set goals, or the implementation gap. The figure shows plainly how limiting global warming to 1.5°C is a goal that remains strongly out of reach.[3]

Figure 1: Warming projections by Climate Action Tracker[4]

The year 2023 will be important for global climate governance since it marks the very first ‘global stocktake’. At COP28 in November, all parties to the Paris Agreement will come together in the United Arab Emirates to reflect on the collective progress towards the Paris goals.[5] This is one of the pivotal moments in the Paris Agreement’s timeline. This very first global stocktake will not only clarify the procedure that is meant to be repeated every five years, but it will also have to fulfil its main function for the very first time: serving as a catalyst for increased ambition.

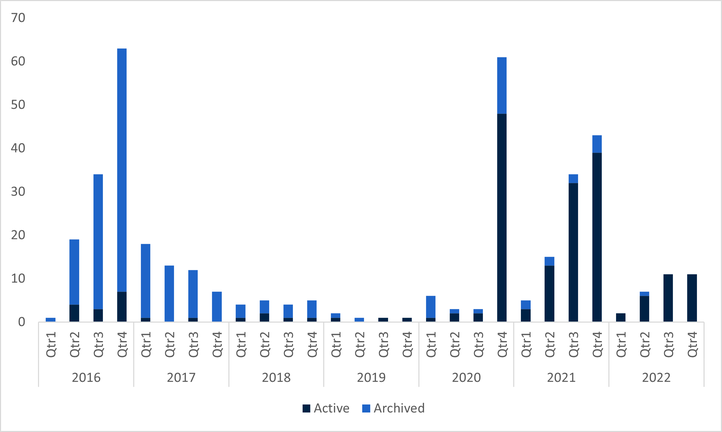

Overall, the Paris Agreement has coincided with increased ambition. On one hand, we see that most parties are actively involved in the regime and complying with its procedures. This is exemplified in figure 2, which shows most parties submitting their first climate plans and adding new updates to these NDCs within the set 5-year timeframe. This is also verified in the 2022 NDC Synthesis Report by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)[6], confirming that 94% of all Parties are providing the necessary information to facilitate the Paris processes. Aside from procedure, the revised pledges have also been steadily increasing in ambition, with the 2022 updates leading to about 9.5% less emissions in 2030 than their 2021 counterparts.[7]

Figure 2: NDC submissions until January 3, 2023[8],[a]

The ambition gap remains steep, however. The gap between unconditional NDCs and the 1.5°C scenario is about 23 GtCO2e[b] and the gap between the 2°C scenario is about 15 GtCO2e.[9] For reference: the average total yearly emissions between 2010 and 2019 was 54.4 GtCO2e. Additionally, there are cases where countries slid back in their climate ambitions, garnering media attention as well as legal action. In Mexico, Greenpeace México won a lawsuit against the Mexican authorities, revoking the submitted 2020 climate target for being less ambitious than the 2016 revised climate plans.[10] This is a concrete example of how domestic climate litigation has made the multilateral Paris Agreement more enforceable.[11]

Though the procedures of the Paris Agreement are progressing as expected, critics are increasingly calling not just for revised climate plans to decrease the ambition gap, but to back up the plans with tangible actions to deal with the implementation gap.[12]

At COP27, the 27th meeting of the Parties to the UNFCCC in November 2022, implementation took centre stage, underlined by the motto ‘Together for implementation’. The COP agreement was dubbed the ‘Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan’.[13] However, instead of concrete policy plans and accomplishments such as a statement on the phase-out of fossil fuels, the agreement merely built on what was done before.[14] The silver lining was the proposed climate fund for loss and damage, which will now have to be developed further in preparation for COP28.[15]

To make the implementation gap more concrete: the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) found in 2022 that the implementation gap for emissions in 2030 is about 3 GtCO2e and 6 GtCO2e for the unconditional and conditional NDC scenarios respectively.[16] These gaps had even increased compared to 2021 because ambitions were raised ahead of policy change. This gap combined with the significant ambition gap, shows the breadth of the challenge ahead.

Is the crisis increasing pressure?

Global climate policy in response to climate change has two significant gaps to face. Countries worldwide need to raise ambition in their climate plans in order to bridge the gap to limit global warming to 2°C and 1.5°C. Additionally, there is a dire need for policy to meet the ambitions set in climate plans, to actually implement the change needed.

Regarding climate ambition, the question remains how countries will update their NDCs during and following the crisis. The EU has already committed to updating its NDC to reflect raised ambitions in their ‘fit for 55 package’.[17] United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has also planned to convene a ‘Climate Ambition Summit’ in September 2023, ahead of COP28, to support more ambitious climate action.[18]

Direct climate policy has been severely influenced by the energy crisis. As other entries in this volume also mention, the war and resulting energy crisis meant an increased need for EU-member states to diversify energy supplies, looking for alternatives for Russian gas. Though a number of EU-member states reverted to coal-fired plants to shift away from Russian gas, coal exit strategies and targets do remain in place. This means that, even if the current shift to coal may lead to a short-term emissions increase, its long-term impact will be trivial.[19] In the long-term, the IEA has noted, renewable power is also being turbocharged, driven by the want of countries to become more self-reliant in their energy generation.[20]

Another element of global climate action and ambition is the impact of the crisis on climate finance. In order to deal with historical climate injustices and appeal to the UNFCCCs creed of ‘Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities’. The promise was made in the 2009 Copenhagen Accords, and formalised in the 2010 Cancun Agreement, for developed countries to provide developing countries with 100 billion USD in climate finance by 2020.[21] This deadline was not met, though there are voices saying 2023 is the year the goal will finally come within reach.[22] The energy crisis and resulting rise in inflation in many countries has wide-reaching impacts on this global financial regime, as well as national and transnational investment in emission mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage.[23] A tight investment climate and distributional effects are just some of the factors that could slow down projects like investments in renewable energy sources. It is also yet to be seen how the Loss and Damage fund (introduced at COP27) will fit into the already fragmented global climate finance regime.[24]

Conclusion

Is the global climate action bubble popping? There is an undeniable need to strengthen commitments and close the ambition gap, as current climate plans still do not limit global warming to the symbolic 1.5°C. More than that, there is the looming implementation gap. This means a need for swift and concrete action to implement these pledges. It is especially on this implementation front that the energy crisis has a risk of creating dents in current policy that could be felt far more in the future. There are however positive trends as well, with the energy crisis providing a boost to the renewable energy transition.

The current climate pledges stand where they are, with short-term and long-term goals that need significant increases. It is the action today that determines if they will pop come 2030 and 2050.

Footnotes

[a] Notes: Nationally Determined Contributions are archived when new (active) plans are submitted to the UNFCCC secretariat.

[b] Gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions.

Endnotes

[1] Jessica Rawnsley, "Food and energy crises threaten to distract from climate talks," updated October 10, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/6f352052-f2bc-401a-beed-b89d9e98a23d.

[2] Daniel Bodansky, "The Paris Climate Change Agreement: A New Hope?," The American Journal of International Law, April, 2016.

[3] Adam Vaughan, "The world's 1.5°C climate goal is slipping out of reach - so now what?," NewScientist, updated June 7, 2022, https://www.newscientist.com/article/2323175-the-worlds-1-5c-climate-goal-is-slipping-out-of-reach-so-now-what.

[4] Climate Action Tracker, "Massive gas expansion risks overtaking positive climate policies," updated November 10, 2022, https://climateactiontracker.org/publications/massive-gas-expansion-risks-overtaking-positive-climate-policies/.

[5] Jamal Srouji, Nate Warszawski, and Hannah Roeyer, "Explaining the First “Global Stocktake” of Climate Action," World Resources Institute, updated November 7, 2022, https://www.wri.org/insights/explaining-global-stocktake-paris-agreement.

[6] UNFCCC Secretariat, Nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement; Synthesis report by the secretariat (October 26 2022), https://unfccc.int/ndc-synthesis-report-2022.

[7] UNFCCC Secretariat, NDC Synthesis Report 2022.

[8] NDC Registry, UNFCCC, "NDC Registry," n.d., https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/NDCStaging/Pages/Home.aspx.; red line indicates the end of a 5-year period from the 3rd quarter of 2022, thus the expectation of submitting updated NDCs.

[9] UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window - Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies, United Nations Environmental Programme (Nairobi: United Nations Environmental Programme, 2022), https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2022.

[10] Climate Action Tracker, "Mexico," updated 5 July, 2022, https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/mexico/targets/.

[11] Lennart Wegener, "Can the Paris Agreement Help Climate Change Litigation and Vice Versa?," Transnational Environmental Law 9, no. 1 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102519000396, https://www.cambridge.org/core/article/can-the-paris-agreement-help-climate-change-litigation-and-vice-versa/5740A983674D197C6F070B081ADAB400.

[12] Katie Kouchakji, "The climate crisis: are we building back better?," International Bar Association, updated November 29, 2022, https://www.ibanet.org/The-climate-crisis-are-we-building-back-better.

[13] United Nations, "Delivering for people and the planet," United Nations, updated n.d., 2022, https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop27.

[14] Amir Sokolowski and Pietro Bertrazzi, "The COP27 agreement is far from a plan for implementation, but non-state actors can help bridge the gaps," updated December 8, 2022, https://www.cdp.net/en/articles/governments/the-cop27-agreement-is-far-from-a-plan-for-implementation-but-non-state-actors-can-help-bridge-the-gaps.

[15] Climate Action Network and The Loss and Damage Collaboration, "Briefing: Towards a Glasgow Dialogue that matters," updated May, 2022, https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/can_ldc_briefing_towards_a_glasgow_dialogue_that_matters.docx.pdf.

[16] UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window - Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies.

[17] Kate Abnett, "EU tells COP27 it will increase climate ambition," updated November 15, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/eu-tell-un-summit-it-plans-raise-climate-target-2023-source-2022-11-15/.

[18] IISD, "UN Secretary-General to Convene “Climate Ambition Summit” in 2023," updated December 21, 2022, https://sdg.iisd.org/news/un-secretary-general-to-convene-climate-ambition-summit-in-2023/.

[19] Sarah Brown, "Coal is not making a comeback: Europe plans limited increase," updated July 13, 2022, https://ember-climate.org/insights/research/coal-is-not-making-a-comeback/.

[20] IEA, "Renewable power’s growth is being turbocharged as countries seek to strengthen energy security," updated December 6, 2022, https://www.iea.org/news/renewable-power-s-growth-is-being-turbocharged-as-countries-seek-to-strengthen-energy-security.

[21] Jocelyn Timperley, "The broken $100-billion promise of climate finance — and how to fix it," updated October 20, 2021, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02846-3.

[22] Valentina Romano, "Climate aid target ‘will be met in 2023’, EU finance ministers say," Euractiv, updated October 6, 2022, https://www.euractiv.com/section/climate-environment/news/climate-aid-target-will-be-met-in-2023-eu-finance-ministers-say/.

[23] Edward Calthrop, "Energy crisis makes public banks even more important," European Investment Bank, updated November 11, 2022, https://www.eib.org/en/stories/energy-crisis-net-zero-transition.

[24] Arthur Wyns, "COP27 establishes loss and damage fund to respond to human cost of climate change," The Lancet Planetary Health (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00331-X.