We Are Here Because You Were There - A Postcolonial Critical Discourse Analysis of the New Pact on Migration and Asylum

By Sira Blancquaert

Promoted by Prof. dr. Jan Orbie

[December 2022]

On the 23rd of September 2020, the European Commission (EC) presented its ‘New Pact on Migration and Asylum’ (hereafter, the New Pact or simply ‘pact’). The pact builds on previous legal instruments that have guided EU migration and asylum policy from the 1990s onwards.[1] For this reason, the framing of the pact as ‘new’ has been critiqued by many scholars.[2] Moreover, the EC has attempted to push negotiations forward on several ‘hanging’ proposals that have been stuck in a political deadlock since 2016.[3] Nonetheless the EU has promised that the New Pact entails a ‘fresh start on migration’, bringing together policy in the areas of migration, asylum, integration and border management. It promises a comprehensive ‘end-to-end European approach’ for the management of migration and asylum. Importantly, according to Ilva Johanssen, within this 'fresh start on migration', the EU will "fundamentally protect the right to seek asylum". Moreover, Johansson promised ‘no more Moria’s.[4]

These promises stand in stark contrast with the critiques from civil-society-; human rights organizations, press and academia. The EU has been condemned because of its violent responses toward asylum seekers and migrants with many authors pointing towards an ‘exclusionary and restrictive turn’ in EU migration and asylum governance. The exclusionary politics of asylum include policy measures aimed at preventing asylum seekers from arriving and preventing those who do manage to cross the EUs external borders from claiming asylum.[5] Asylum seekers are prevented from working, traveling or living in a city of their choosing. Those whose claims are deemed unfounded are detained and deported back to unstable countries with poor human rights records.[6] Moreover, the general response to asylum seekers and migrants translated into extreme practice of border violence such as push backs, involuntary detentions, abuse, hot spots, neglect, the 'letting die at sea' by criminalizing search and rescue operations (SAR)…[7] It is argued that any notion of the international protection standards for asylum seekers, as established under the Geneva Conventions, seems to be abandoned. The result is a complete downgrade of the supposedly universal human right to asylum.[8]

So how are we to make sense of this contradiction? If the EU is to really and fundamentally protect the right to seek asylum, we might suspect that ‘real change is underway’ and that the EU will make a 'U-turn' regarding their treatment of migrants and asylum seekers. The objective of this research is simple: to establish whether or not the EU can live up to this ambitious task. Concretely, this paper seeks to examine whether or not the New Pact will fundamentally change the EU migration and asylum regime in the sense that it will fundamentally protect the right to asylum, as Johansson has promised. Following postcolonial arguments this right has never been actually protected by most European institutions and member states.[9] If the New Pact really promises to fundamentally protect the right to seek asylum, then this would require a paradigm shift of the 'third order'.[10] In other words, this would mean that the New Pact entails a significant breakaway from the current paradigm in the sense that it would challenge the (colonial/) ideological underpinnings on which current policies are built.[11]

Therefore, the research question is as follows: does the New Pact on Migration and asylum point to a paradigm shift in EU migration and asylum policy?

In the next section the EUs migration and asylum governance will be discussed from a postcolonial perspective. While in section two the current policy paradigm will be mapped-out from a postcolonial framework building on Lucy Mayblin's book 'Asylum after Empire: Colonial legacies in the politics of asylum seeking'. In section three the New Pact itself will be examined using Postcolonial Critical Discourse Analysis (PCDA) and analysed against the current policy paradigm.

A postcolonial reading of the EUs migration and asylum governance

On the one hand the EU claims that it has guided its policy developments on the Geneva convention thus fulfilling its duties as prescribed by international obligations. More harmonization would lead to a more effective asylum system and thereby benefiting the right to seek asylum.[12] On the other however, that exact right to seek asylum is said to be violated on a daily basis through the ‘translation into practice’ of the policies installed by the EU to govern the mobility of people from the global south seeking refuge or a better life within Europe's borders.[13] Diving into all the different explanations given for this ‘downgrading’ of the right to seek asylum is beyond the scope of this paper. However, and more importantly when we approach the EUs migration and asylum governance from a postcolonial perspective, it becomes clear how firstly policy is devoted to keeping as much people from the global south out at all cost to ensure that the mobility of people from within the EU is protected and secondly how this is legitimized through discourses in which some people are deemed more worthy than others. In other words, it is argued that what is said to be ‘a universal human right to asylum’ was never intended for people from the global south but merely for the ‘prima facia refugees’, namely Europeans fleeing both world wars as well as Cold War refugees fleeing communism.[14]

Davies and Isakjee argue that in order to make sense of these contemporary inequalities, social theorists must look back to those histories of governance that were characterized by racial exclusion and racist discourse.[15] When doing so, one can trace Europe’s 'migration crisis' as part of its ongoing encounter with the world of empire, colonial conquest and slavery, it created over 500 years ago. A connection that is made all the more tangible through migrants’ resistance, chanting 'We are here because you were there'.[16] We thus have to look at those histories of colonialism, when race was the principle marker of subjectification if we are to make sense of a regime of governance often claimed to be humane but of which the practical translations show a different story.

First and foremost, it is important to acknowledge the fact that non-Europeans were purposefully excluded from the Refugee Conventions. Put differently, the legal framework for protecting refugees was only intended for and applicable to those displaced in Europe.[17] Secondly, the legacies of colonialism for mobility and immobility also tend not to be acknowledged. The models of restricting people’s movements were invented in the colonies to restrict the movement of the colonized.[18] As Kalir also argues colonial practices involved restricting the mobility of colonized peoples and facilitating the mobility of the colonizers. Even though the world, and consequently also the formerly colonized, had become more mobile through processes of globalization, legal and practical barriers have been put into place to re-inscribe the very immobility of the formerly colonized. [19] Mayblin explains how citizenship itself depends on controlling mobility because the sedentary ideology of the nation state cannot co-exist with the reality of human mobility.[20] De Genova has called this reality ‘the autonomy of migration’ of which he argues has been a constant throughout human history.[21] The nation state on the other hand, needs borders and immobility in order to exist. However, when the image of stability of the nation-state is established, the growing mobility of a particular group of people (ie: citizens) can be facilitated on the prerequisite that the mobility of others, ‘the non-belonging’ (ie: non-citizens) is restricted.

Importantly, Mayblin argues that immobility is not only about non-movement, it requires restricting people’s access to human rights. Legacies of colonialism have produced the ideas of undesirable and excludable asylum seekers.[22] Restricting certain people from accessing their human rights ultimately requires assigning differential value to the lives of human beings. Generally postcolonial literature states that the hierarchical conceptions of human worth, produced for and by colonial conquest, remains a dominant (and colonial) worldview in the realm of international politics. Within this worldview some societies are modern while others are 'traditional' and 'backward', always delineated on 'them' being racially and culturally alien to Europe. Decolonial scholars have termed this coloniality/modernity, which not only refers to whole countries or regions as being backward but also to people from the Global South, in this case the migrants themselves, in the sense that they embody the backwardness and are always perceived as being racially and culturally alien to Europe. Through the awarding of a sense of 'unmodernity' to the bodies of migrants and asylum seekers, they become the disposable, their lives 'expandable', the easily impoverished and exploitable. On these grounds they are denied their humanity. Importantly, it is argued that this way of thinking is inherent to liberal western values, and not, as if often claimed, something of the past.[23]

Even though it is true that the undisguised brutality of colonial governance is something of the past, the subtler and lesser visible forms of denying the humanity of certain peoples continues. Thus the idea of white-superiority is a worldview in itself that is still very much part of European reality.[24] To this extent Kalir argues that these believes are still deeply embedded in contemporary discourses on asylum seekers. The differential valuation of lives by which human rights are only ‘universal’ when they apply to white lives and seem to lose any notion of universality when applied too black and brown, mostly Muslim lives lies at the very core of Europe’s contemporary treatment of asylum seekers and migrants. The difference with past colonial governance is that these restrictions on certain populations' mobility can no longer be achieved in the context of colonially defined spaces of immobility. However contemporary restrictions can be achieved and are aimed to be achieved through the racial politics of border governance. Within European border governance, mobile black and brown bodies still represent these subject races.[25] They become legally re-categorized as 'migrants'.[26] This was thus produced by and re-produces an unequal and profoundly racialized mobility regime in which the movement for some depends on the containment of others.[27] This basic distinction between awarded mobility and imposed immobility lies at the core of the EUs migration and asylum regime and has been institutionalized through the Schengen treaties. The creation of the EUs Schengen zone of free movement of persons, goods and capital for European citizens had as its direct consequence a reinforced exclusion of citizens of the global South.[28]

The current EU migration and asylum policy paradigm: the non-entree regime

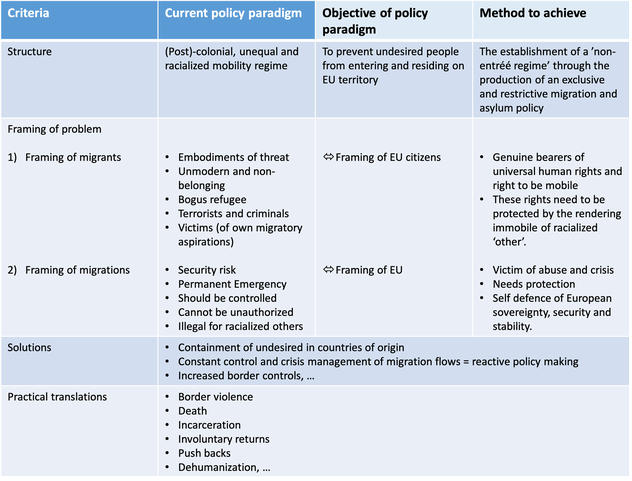

To make up the current policy paradigm five criteria were identified. The regime or structure is given a name, its objective and the method to achieve that objective are also identified. Then the most dominant ways in which migrants and migration are framed by EU-ropean politics are identified as well as the binary oppositions through which EU citizens and the EU itself are described. The framing of migrants and migration serves as a framing of 'the problem' and the binary oppositions serve as the given reasons as to why these pose a problem for the EU and its citizens. The fourth criteria then are the given solutions on how the EU and its member states should deal with these problems. Lastly an overview of the practical translations of the current policy paradigm, presented in figure 1, are discussed.

Figure 1: The current policy paradigm

As explained above, through the unequal and racialized mobility regime, certain peoples are awarded the privilege of being mobile while others are not. Their immobility then becomes a prerequisite for the mobility of others. Much in the same way as the mobility of EU citizens within the EU depends on the immobility of non-Europeans, namely migrants and asylum seekers from the Global South. The objective of the unequal and racialized mobility regime is thus to prevent the undesired, the disposable, the non-belonging from entering and residing on EU territory.[29] This is achieved through the development of a restrictive and exclusionary migration and asylum policy which has been in the making ever since the 1990s.[30] This is aided through discourses on migrants and migration in which discursive classifications are used to frame both as problems. These problems then should be solved through proposed solutions taking the form of reactive policy developments.[31] Both the framing of migrants and migration have their own binary oppositions namely a discursive framing of EU citizens and their 'mobility rights' and a framing of the EU as to how a restrictive and exclusionary migration and asylum policy is legitimized and why it is necessary.

Framing migrants and migrations as a problem and how to solve it.

Davies and Isakjee argue that mobile black and brown bodies are framed as the visual embodiments of threats to European sovereignty. The logics of modernity, mobility and citizenship are fundamental rights for the 'native' European while they remain "a precious and scarcely distributed gift to those outside its political borders.[32] Moreover, the binary opposition between modern and unmodern also serves to reproduce the classification of a group of people as the 'non-belonging', those that will never earn or gain those rights.

Postcolonial thought shows that this framing of migrants and dominant logic of the politics of asylum always occurs on racialized lines. As De Genova explains in the context of the 'migration crisis' people were first seen as refugees and became an object of compassion and protection. However, this quickly changed into a discourse turning refugees into 'mere migrants'. Herein the term asylum seekers itself is always predicated upon a basic suspicion that the majority is lying about their asylum claims producing the image of the 'bogus refugee'. On the one hand the EU victimizes itself, being a victim to the countless people accused of abusing their "humane hospitality".[33] On the other however, it is important to acknowledge that it seems as though these people are not seen as the "genuine bearers" of any presumptive and supposedly universal human right to asylum. Instead they are always under suspicion of deceit. This all occurs against the background of a European asylum system that "routinely and systematically disqualified and rejected the great majority of applicants, and thereby ratifies anew the processes by which their mobilities have been illegalized".[34] Moreover, De Genova argues that the depiction of refugees as migrants was a crucial discursive manoeuvre which has caused European authorities to promise the expulsion of those who became migrants. They were deemed unwelcome, presumed to be irregular, making them deportable. Finally, 9/11 and several terrorist attacks within the EU have prompted the framing of refugees as terrorists. Moreover, the fact that most are now seen as illegally having entered the EU has invoked the sense that they are also criminals.[35] Lastly, authors within the debates on military humanitarianism have pointed to the discursive framing of migrants as being victims of their own migratory aspiration by which they fall victim to human trafficking.[36] The complete lack of legal pathways into Europe and its often deadly consequences are thereby obscured.[37] The framing of migrants as victims also serves to reproduce the image of a humane and caring EU-rope. It serves to justify calls for more protection in the region, or in other words containment, because if migrants are contained and offered enough humanitarian assistance in their own regions they do not have to take dangerous routes and cross dangerous borders and expose themselves to the many risks these entail. In that way it is not the EU that is to blame for the countless deaths at its borders, but the migrants themselves who attempt those crossing.[38]

Migration itself, especially African migration was often framed in media and political discourse as an 'invasion' or a 'plague'.[39] Ultimately all migration became seen as a security risk to the stability of the EU, even becoming a contradiction to the EU-ropean space of fundamental freedom, security and justice and threatening the survival of Schengen.[40] This has led to the growing need to control and manage migration. This management rhetoric gained premise under the New Asylum Paradigm.[41] Containment measures were proposed to achieve the aforementioned goal of limiting access to specific group of asylum seekers and thereby restricting access of the majority of people. Cantat et al then argue that this securitarian framework evolved into perceiving migration in terms of crisis, referring to a state of permanent emergency.[42] The need to 'manage' and 'control' migration then evolved into a constant governance of 'crisis management', becoming the routinized and normalized way of dealing with and responding to migration. This has also prompted postcolonial scholars to argue that this mode of governance has made the development of the policy domain itself to be driven by crisis and is therefore inherently reactive.[43] Importantly Cantat et al hint at the fact that the crisis-talks and consequently need to manage the crisis only seems to apply to South-North mobility. When migration is only perceived as a crisis when defined in terms of South-North mobility it provides a legitimization for shrinking responsibilities in refugee protection.[44] This becomes clear when looking at the externalization of migration management and control. The New Keywords Collective shows how the EU, while claiming that the ‘crisis’ always originates from outside its borders, produces a justification for externalizing the responsibilities to deal with the crisis in the form of ‘safe third countries’ and protection in the region. In this discourse the EU presents itself as an innocent victim that needs to protect itself from the personification of external crises, namely migrants. Non-Europeans bear with them dangerous, possible crisis inducing traits. Leaving them to move unauthorized would cause instability. This can be prevented by containing, managing and controlling their mobility within the territory of the Union or simply preventing them from ever setting foot on that territory. The framing of migration as a 'security risk'; a 'permanent emergency'; as something that needs to be controlled and should never be unauthorized serves to produce the exact mode of governance that makes being mobile or having any 'migratory aspiration' illegal for racialized others.[45] This is what Mayblin calls the ‘non-entrée regime’.[46]

These discursive framings thus provide the basis of the current policy paradigm. They each serve to legitimize proposed solutions of which the ultimate result is that the right to seek asylum is being downgraded on every level. Moreover, the lack of legal pathways into Europe make sure that there is no other option than to apply for asylum even when the applicant in questions does not have the right legal reasons to do so.

The New Pact and its promises.

The New Pact has been presented by the Commission as the much needed 'comprehensive approach' to migration. Consisting of the EU-ropean solutions for the abovementioned problems, while also ensuring that the right to seek asylum is fundamentally protected through its implementation. The New Pact will now be analysed against the backdrop of the current policy paradigm. The ways in which migrants and migration on the one hand and the EU and its citizens on the other are framed will be compared with those displayed in figure 1 and as explained above. As well as the ways in which the proposed solutions will or will not fundamentally protect the right to seek asylum. As has been argued in the introduction: If the New Pact really promises to fundamentally protect the right to seek asylum, then this would require a paradigm shift of the 'third order'.[47] In other words, this would mean that the New Pact entails a significant breakaway from the current paradigm in the sense that it would challenge the (colonial) ideological underpinnings on which current policies are built.[48]

Delputte and Orbie who wrote on policy paradigms within EU development policy discuss what is needed in order for a paradigm shift to take place. Important to note here is that one can only claim a paradigm shift has taken place when the change is of a 'third order'. This refers to Hall's classifications of first, second and third order changes. The first and second order changes, with the former referring to adjustments in the settings of existing instruments and the latter to innovations at the level of the instruments themselves, should be considered as 'normal policy making'. Meanwhile, a 'third order change' entails ‘radical changes in the overarching terms of policy discourse associated with a ‘paradigm shift’.[49] This thus refers to a change within the 'underlying philosophies' that guide public policy.[50] These underlying philosophies are stubborn and therefore rarely contested. For a change of such a nature to take place Delputte and Orbie identify three necessary conditions. Namely the existence of a sense of policy failure, the search for alternative policies to solve the failure of the existing policy and lastly a power shift through which supporters of the new paradigm gain the authority to institutionalize it through the development of new policies and instruments.

To a certain extent, these do apply to the New Pact. The current composition of the European Commission took office in November 2019. Both Juncker and von der Leyen expressed the need for a 'new policy on migration'[51] and a 'fresh start on migration'.[52] Some changes to the previous Commission are notable. For example, Commissioner Avramopoulos was replaced by Ylva Johansson. Even though their responsibilities and goals seem more or less the same, Johansson has promised to 'fundamentally protect the right to seek asylum'. Within its communication, the Commission has acknowledged the current failure of the Dublin II regulations and has pointed out that the ways in which the EU and individual member states responded to the 'migration crisis' of 2015 lacked a comprehensive approach which lead to ad-hoc decision making and even put the survival of the Schengen Zone in question.[53] The New Pact then serves as the answer to the abovementioned problems in that it "contains a number of solutions through new legislative proposals and amendments to pending proposals to put in place a system that is both humane and effective, representing an important step forward in the way the Union manages migration".[54] While it would be fruitful to analyse to what extent the New Pact entails a first or second order change this is beyond the scope of this paper.

Not just ‘new wine in old bottles’

In its entirety, the New Pact should provide the EU and its Member States with the ability to provide 'European solutions' It is stated that "the challenges of migration management, including those related to irregular arrivals and return, should not have to be dealt with by individual Member States alone, but by the EU as a whole. A European framework that can manage the interdependence between Member States’ policies and decisions is therefore required".[55]

The New Pact is made up of nine goals (p. 2) [a]:

- a robust and fair management of the EUs external borders;

- fair and efficient asylum rules, streamlining procedures for asylum and return;

- a new solidarity mechanism for situations of SAR, pressure and crisis;

- stronger foresight, crisis preparedness and response;

- an effective return policy and an EU-coordinated approach to returns;

- comprehensive governance at EU level for better management and implementation of asylum and migration policies;

- mutually beneficial partnerships with key third countries of origin and transit;

- developing legal pathways for those in need of protection and to attract talent;

- supporting effective integration policies.

The analysis is centred around these goals because the New Pact is presented in such a way that these goals make up its constitutive elements promising 'an end-to-end approach' and the needed 'European solutions' the current stalemate and ad-hoc policy developments that taunt current asylum and migration management (p. 28).[56] The whole of the New Pact should "ensure a seamless link between all stages of the migration procedure from a new pre-entry procedure to the return of third-country nationals and stateless persons without a right to remain in the Union".[57]

The first goal on a 'robust and fair management of external borders' is said to be crucial in the fight against unauthorized movements and to ensure a well working 'integrated border procedure' which relates to the second goal of implementing 'fair and efficient asylum rules, streamlining procedures for asylum and return'. The first is focused on irregular migrants already residing in EU territory while the latter is focused on irregular arrivals. Both are part of the same overarching goal. Namely to prevent their entry onto EU territory and to return those who did manage to allude border controls and are now 'moving unauthorized' within the territory of the Union.

Unauthorised movements are framed as a 'danger', as 'affecting the credibility of the entire EU system' (p. 10 - 11) and mainly seen as a consequence to the 'current shortcomings in the management of borders' (p. 3). Within the New Pact the discourse 'ingenuine refugees' is used to paint an image of 'scheming asylum seekers' who are well aware of the current weaknesses and loopholes in the system. They are seen as abusing that system and by doing so they are framed as a threat to the sustainability of the Schengen Area. The Schengen area then is said to be the greatest achievement of the EU that is now being 'put under strain by unauthorized movements'. Therefore, the New Pact proposes a 'New Solidarity Mechanism' to close those loopholes and to ensure that "the rules on responsibility for examining an application for international protection are refined to make the system more efficient, discourage abuses and prevent unauthorized movements" (p. 6).

The second goal, streamlining procedures for asylum and return, serves to achieve the apprehension of irregular arrivals and preventing them from moving unauthorized on EU territory. It is centred on the implementation of 'an integrated border procedure' which is said to be closing "the gaps between external border controls and asylum and return procedures" (p. 4). Again migrants and asylum seekers are framed as taking advantage of those gaps, thereby consciously abusing the EU-ropean migration and asylum system and putting national systems under pressure. The EU is a victim of that abuse and the New Pact serves as the answer to close the existing loopholes in such a way that no asylum seeker or migrant can continue abusing it. Within the proposed 'integrated border procedure a pre-entry screening will determine whether or not a person is allowed to seek asylum. It is claimed that only those really in need of protection will remain after the asylum procedure is concluded. Those with no right to stay will be 'swiftly returned' under the return procedure. The Commission states: "This would eliminate the risks of unauthorized movements and send a clear signal to smugglers. It would be a particularly important tool on routes where there is a large proportion of asylum applicants from countries with a low recognition rate" (p. 4). The asylum procedure then applies only to those 'who might have founded claims'. During the entirety of the procedure the applicant does not 'legally set foot on EU territory'. In this light, Mouzourakis has argued that the main objective of the Screening and Asylum Procedure Regulation is to prevent people from entering the EU, and that detention becomes an automatic necessity to provide Member States with the ability to 'swiftly return' those with 'misleading' or 'unfounded' claims.[58] The whole system centres around the belief that "EU migration rules are only credible when those who do not have a right to stay in the EU are effectively returned" The underlying rhetoric here is again the belief that most asylum seekers are ingenuine. The sooner they are apprehended, the smaller the risk of unauthorized movements and irregular stays. It is clear that the migrants themselves and migration in general are framed as the causes of the 'crisis' the EU has undergone since 2015. The EU does not take any blame in the matter. On the contrary they blame those of who it is said that they abuse and circumvent the system which puts pressure on member states and their national asylum systems. Within this discourse the Commission produces a binary opposition between 'genuine and ingenuine refugees' since the 'abusers' of the system are framed as preventing those really in need of international protection.

However, as postcolonial theory shows the basic suspicion that the majority is lying about their asylum claims and producing the image of the 'bogus refugee', happens against the background of a European asylum system that "routinely and systematically disqualified and rejected the great majority of applicants, and thereby ratifies anew the processes by which their mobilities have been illegalized.[59]” This thus points to the argument that even those really in need of international protection are 'routinely and systematically rejected'. Thereby downgrading the 'presumptive and supposedly universal human right to asylum'.

The third goal relates mostly to the new solidarity mechanism, which allows Member States to choose in which way they will fulfil their compulsory solidarity. However, what is notable here is the recommendations made by the Commission regarding SAR. It is said that the arrivals following SAR disembarkations puts a strain on coastal Member States. Again the binary opposition between the EU as a victim of the migratory aspirations of those 'having no right to stay' is produced.[60] The same applies for the Regulation addressing situations of crisis and force majeure and recommendation on a crisis blueprint, mostly represented within the fourth goal. It is said that the EU needs: "actively engaging in conflict prevention and resolution as well as to keep each other alerted of a potential crisis in a third country, which could lead to a migration crisis within the EU.”[61]

Again the EU is the innocent victim that needs to protect itself from migrants who, also in the abovementioned quote are framed as the personification of external crises. The crisis refers to migration crisis defined by the Commission as: "any situation or development occurring inside the EU or in a third country having an effect and putting particular strain on any Member State’s asylum, migration or border management system or having such potential".[62] Importantly, this framing hides an important critique. Namely, as Cantat et al. have shown, crisis-talk serves to the establishment of particular forms of governmental intervention that have more in common with authoritarian measures than with policies developed within the normal procedures of democratic debate and deliberative processes.[63] This is represented by the Regulation addressing situations of crisis and force majeure because it allows for a temporary derogation from normal procedures and timelines in times of crisis. Mouzourakis has argued that this would allow Member States an extensive margin to shrink their responsibilities under loosely defined circumstances of crisis and force majeure.[64]

The fifth goal is an overarching one that stresses again the need for a European Approach through which national policies are coherent to the European approach. The Commission plans to introduce several EU-level coordinators and instruments. The focus lies mainly at preventing unauthorized movements and guaranteeing an effective return policy. This is to be achieved through the instalment of a EU return coordinator and a High Level Network for return. Also fitting within the 'prevent and return' logic is the proposed 'change in paradigm' in cooperation with non-EU countries. This refers to the 'whole route approach' and is clearly situated within the 'prevention and return' objective of the current policy paradigm.[65] It is stated that one of the key gaps is the difficulty to return those who do not voluntarily return (p. 21). The Commission intends to deepen current partnerships with non-EU countries in order to prevent and return those 'having no right to stay' before they attempt 'dangerous and life threatening' crossings. Thereby the discourse of victimizing migrants is reproduced and feeds into the logic of preventing deathly border encounters by reducing the number of people able to make those crossings by apprehending them 'on route'. This justifies cooperation with non-EU countries for protection in the region, the 'joint management of mixed migration flows' and the fight against smuggling. In connection to migrants as the personification of crises explained above, the New Keywords Collective stated that this discourse allows the EU to externalize its responsibilities through partnerships.[66]

Regarding the seventh goal an interesting new category of asylum seeker is developed. That of the 'privileged asylum seeker' being awarded an exemption from the border procedure, not having to prove their genuineness. This shows most clearly how the differentiation between wanted and unwanted migrants is translated into practice through the integrated border procedure. This procedure is mainly intended for irregular arrivals, and highly focused on return.[67] However, the Commission promises to provide legal pathways to a distinct group of asylum seekers. Namely the most vulnerable of which children are a key priority. These most vulnerable make up a section of the wanted migrants with attracting skilled and talented migrants making up the other. While unwanted migrants are illegalized and framed as abusers of the system these wanted migrants are awarded legalization. Talented and skilled migrants are to be attracted through the development of 'talent partnerships' with third countries.[68] Attracting those 'talents' has become a key priority in the New Pact as the EU risks to lose “the global race for talent.” On the other hand, there is the group of 'privileged asylum seekers' or the most vulnerable who are to be offered the needed protection through an exemption from the border procedure on the one hand and through the introduction of the immediate protection status. This is based on the current temporary protection directive (TPD). This is important because the TPD has only recently been used for the first time since its creation to respond to the Ukrainian refugees. Ciger, working on the TPD and the question 'why now' came to the simple conclusion: "Ukrainians are Europeans but Syrians, Afghans, Tunisians, Libyans, Iraqis were not..." This makes all the more sense when seen within the light of a postcolonial analysis of whom were seen as the intended beneficiaries of the Refugee Conventions and who were not.[69]

Within the New Pact it is argued that the whole end-to-end approach is based on fairness and humane-ness fully in line with European values and morals. However, those same values are then framed as being under threat due to unauthorized movements and irregular migrants. They then serve as a justification to inflict inhumane treatment on those irregular migrants in which detention becomes the norm. Instead of fundamentally protecting the right to seek asylum, as Ylva Johansson promised, the New Pact causes the right to seek asylum to deter substantially.

Conclusion

This dissertation sought to uncover in what ways the New Pact offers a 'fresh start on migration' in the sense that it 'fundamentally protects the right to seek asylum'. To do so I have developed a framework that maps the current policy paradigm against which the New Pact can be analysed. Based on secondary literature, existing theories on paradigms within the EUs migration and asylum regime and postcolonial theory it became clear that all movement from the global South to the EU is perceived in irregular or illegal terms. Illegal means unwanted, as the European Council has made clear during the Tampere Summit of 1999[70] and most recently in June of last year.[71] The EU started to adopt a discourse in which all asylum seekers were presumed to be illegal and ingenuine until proven otherwise. This discourse finds its origins in the colonial histories of racial hierarchization and the need to govern the mobilities of the colonized. In the New Pact these discourses remain present as the primary goal of the New Pact is the differentiation between wanted and unwanted migrants. The treatment these two opposing groups of people deserve is made clear through the distinction between providing legal pathways on the one hand and increasing border controls, the introduction of the Solidarity Mechanism and the integrated border procedure on the other. The unwanted migrants are to be apprehended at the border, 'on route' and inside EU territory. When apprehended they should be prevented from entering the EU until their applications are completed. If the person in question has 'no right to stay' everything should be done to return that individual as 'swiftly as possible'. The institutionalization of wanted versus unwanted migrants will result in a continued illegalization of South-North mobility, will continue to prevent people from exercising their right to asylum and will 'open' the EU only to the 'really deserving'.

Moreover, through the Regulation addressing situations of crisis and force majeure, the Commission institutionalizes the differentiation between ‘normal-’, ‘pressure-’ and ‘crisis-’ times. It allows for a deviation from normal procedures in times of crisis. However as has been shown crisis operates as a discursive category of power underpinned by assumptions of what is good or bad and desirable or undesirable. Coining something as a crisis has a productive dimension in the sense that it structures the world and calls for certain ways to govern it. This 'crisis management' then invokes the justification for extraordinary modes of government. The fact that the Commission wants to implement different 'routinized ways' of dealing with migration depending on the produced level of crisis points to the institutionalization of the crisis discourse. Which as Cantat et al have argued has become inseparable from debates around migration, now finding its way into legislation. Moreover, as the New Keywords Collective have shown this discourse has as its binary opposition the image of an EU that is the innocent victim of 'crises' happening outside its borders. Migrants and asylum seekers originating from those 'crisis places' bear with them those same 'crisis inducing traits', they are unpredictable, unauthorized and threatening and their mobility should therefore be constantly controlled. Within the New Pact this is reflected through the institutionalization of the differentiation between those who are seen as bearing those traits and those who are not. Or in other words, and as mentioned above, a differentiation between wanted and unwanted migrants. Through the introduction of a 'privileged asylum seeker' and the clear goal of attracting talented and skilled migrants on the one hand and the deepening of an asylum system that routinely and systematically rejects the majority of applicants, the Commission makes clear who has a right to stay and who doesn't or who is framed as wanted and who as unwanted.

Footnotes

[a] Citation of pagenumbers without a source all refer to the source: European Commission, ‘COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION on a New Pact on Migration and Asylum (52020DC0609)’, September 23, 2020

Endnotes

[1] European Commission, “A Fresh Start on Migration: Building Confidence and Striking a New Balance between Responsibility and Solidarity (Press Release),” September 23, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1706.

[2] Izabella Majcher, 2020, “The EU Return System under the Pact on Migration and Asylum: A Case of Tipped Interinstitutional Balance?,” European Law Journal 26, no. 3–4 (2021): 199–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12383

[3] European Commission, “Common European Asylum System,” Migration and Home Affairs. n.d., https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/migration-and-asylum/common-european-asylum-system_en.

[4] European Commission, “A Fresh Start on Migration: Building Confidence and Striking a New Balance between Responsibility and Solidarity (Press Release),” September 23, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1706.

[5] Jari Pirjola, “European Asylum Policy - Inclusion and Exclusions under the Surface of Universal Human Rights Language,” European Journal of Migration and Law 11, no. 4, (2009): 347 - 366, https://doi.org/10.1163/157181609789804277.

[6] Lucy Mayblin, Asylum after Empire: Colonial Legacies in the Politics of Asylum Seeking (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017).

Barak Kalir, “Departheid’: The Draconian Governance of Illegalized Migrants in Western States,” Conflict and Society 5, no. 1, (2019): 19–40.

[7] Elspeth Guild, “Promoting the European Way of Life: Migration and Asylum in the EU,” European Law Journal 26, no. 5–6, (2020): 355–70. https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/eulj.12410.

Barak Kalir, “Departheid’: The Draconian Governance of Illegalized Migrants in Western States,” Conflict and Society 5, no. 1, (2019): 19–40.

Violette Moreno-Lax, “The EU Humanitarian Border and the Securitization of Human Rights: The “Rescue-Through-Interdiction/Rescue-Without Protection” Paradigm,” Journal of Common Market Studies 56, No. 1, (2018): 119–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12651.

Julien Brachet, “Policing the Desert: The IOM in Libya Beyond War and Peace,” Antipode 48, no. 2 (2016): 272–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.1217.

[8] Nicolas De Genova, The Borders of “Europe (Amsterdam University Press, 2017).

[9] Ibid; Lucy, Mayblin, Asylum after Empire: Colonial Legacies in the Politics of Asylum Seeking. (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017)

[10] Schmidt in Sarah Delputte and Jan Orbie, “Paradigm Shift or Reinventing the Wheel?: Towards a Research Agenda on Change and Continuity in EU Development,” Journal of Contemporary European Research, 16 no. 2 (2020): 234–56. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v16i2.1084.

[11] Nicolas De Genova, The Borders of “Europe (Amsterdam University Press, 2017); Lucy Mayblin, Asylum after Empire: Colonial Legacies in the Politics of Asylum Seeking (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017); Barak Kalir, “Departheid’: The Draconian Governance of Illegalized Migrants in Western States,” Conflict and Society 5, no. 1, (2019): 19–40; Lucy Mayblin, Mustafa Wake, and Mohsen Kazemi, “Necropolitics and the Slow Violence of the Everyday: Asylum Seeker Welfare in the Postcolonial Present,” Sociology 54 No. 1, (2020): 107–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519862124.

[12] Dimiter Toshkov and Laura de Haan, “The Europeanization of Asylum Policy: An Assessment of the EU Impact on Asylum Applications and Recognitions Rates,” Journal of European Public Policy 20, No. 5 (2013): 661-683, DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2012.726482. ; Christian Kaunert, “Liberty versus Security? EU Asylum Policy and the European Commission,” Journal of Contemporary European Research 5, no. 2, (2009): 148-170; Timothy J Hatton, “Asylum Policy in the EU: The Case for Deeper Integration,” Centre for economic policy research, (2014) http://repository.essex.ac.uk/14920/1/Asylum%20Cooperation%20Revised.pdf

[13] Florian Trauner, “Asylum Policy: The EU’s “Crises” and the Looming Policy Regime Failure,” Journal of European Integration 38, No. 3, (2016):311-325, DOI: 10.1080/07036337.2016.1140756; Sandra Lavanex, “Failing Forward” Towards Which Europe? Organized Hypocrisy in the Common European Asylum System,” Journal of Common Market Studies 56, no. 5 (2018): 1195-1212; Jari Pirjola, “European Asylum Policy - Inclusion and Exclusions under the Surface of Universal Human Rights Language,” European Journal of Migration and Law 11, No. 4, (2009): 347 - 366, https://doi.org/10.1163/157181609789804277; Julien Brachet, “Policing the Desert: The IOM in Libya Beyond War and Peace,” Antipode 48, no. 2 (2016): 272–92, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12176; Rosemary Byrne and Andrew Shacknove, “The Safe Country Notion in European Asylum Law,” Harvard Human Rights Journal 9, (1996): 185-226; Matthew Hunt, “The Safe Country of Origin Concept in European Asylum Law: Past, Present and Future,” International Journal of Refugee Law 25, no. 4 (2014): 500–535, https://doi.org/10.1093/irjl/eeu052; Violette Moreno-Lax, “The EU Humanitarian Border and the Securitization of Human Rights: The “Rescue-Through-Interdiction/Rescue-Without Protection” Paradigm,” Journal of Common Market Studies 56, No. 1 (2018): 119–40, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12651; Eiko R Thielemann, “Why Asylum Policy Harmonisation Undermines Refugee Burden-Sharing,” European Journal of Migration and Law 6 (2004): 47–65; Francesca Ipollito and Samantha Velluti, “The Recast Process of the EU Asylum System: A Balancing Act between Efficiency and Fariness,” Refugee Suvrey Quarterly 30, no. 3, (2011): 24–62; Aladag Görentas, “FROM EU-TURKEY STATEMENT TO NEW PACT ON MIGRATION AND ASYLUM: EU’S RESPONSE TO 21ST CENTURY’S HUMANITARIAN CRISIS,” International Journal of Afro-Eurasion Research, Special issue Migration, (2020): 25–33; Elspeth Guild, “Promoting the European Way of Life: Migration and Asylum in the EU,” European Law Journal 26 no. 5–6 (2020): 355–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12410; Evangelia Tsourdi, “Bottom-up Salvation? From Practical Cooperation towards Joint Implementation through the European Asylum Support Office,” European Papers 1, No. 3 (2016): 997–1031, https://doi.org/10.15166/2499-8249/115.

[14] Mayblin, Asylum after Empire: Colonial Legacies in the Politics of Asylum Seeking.

[15] Thom Davies and Arshad Isakjee, “Ruins of Empire: Refugees, Race and the Postcolonial Geographies of European Migrant Camps,” Geoforum 102 (2019): 214–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.031.

[16] New Keywords Collective, “Europe / Crisis: New Keywords of “the Crisis” in and of “Europe,” Near Futures Online 1, “Europe at a Crossroads”’ (2016) http://nearfuturesonline.org/ europecrisis-new-keywords-of-crisis-in-and-of-eu- rope/.

[17] Mayblin, Asylum after Empire.

[18] Davies and Isakjee, Ruins of Empire: Refugees, Race and the Postcolonial Geographies of European Migrant Camps.

[19] Kalir, Departheid, 2019.

[20] Mayblin, Asylum after Empire, p. 25.

[21] De Genova, The borders of Europe.

[22] Mayblin, Asylum after Empire, p. 26.

[23] Lucy Mayblin, Mustafa Wake, and Mohsen Kazemi, Necropolitics and the Slow Violence of the Everyday: Asylum Seeker Welfare in the Postcolonial Present.

[24] Catarina Kinnvall, “The Postcolonial Has Moved into Europe: Bordering, Security and Ethno-Cultural Belonging,” Journal of Common Market Studies 54, no. 1 (2016): 152–68, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12326.

[25] Kalir, Departheid.

[26] Davies and Isakjee, Ruins of Empire: Refugees, Race and the Postcolonial Geographies of European Migrant Camps.

[27] Deborah Cowen, “Infrastructures of Empire and Resistance,” Versobooks (blog), January 25, 2017, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3067-infrastructures-of-empire-and-resistance.

[28] Charles Heller and Bernd Kasparek, “The EU’s Pact against Migration, Part One,” OpenDemocracy (Blog), 5 October 2020, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/the-eus-pact-against-migration-part-one/; Céline Cantat, Hélène Thiollet, and Antoine Pécoud, “Migration as Crisis. A Framework Paper,” 2020 https://www.magyc.uliege.be/about/wp3/.

[29] Mayblin, Asylum after Empire.

[30] Charles Heller and Bernd Kasparek, The EU’s Pact against Migration, Part One; Kalir, Departheid.

[31] Charles Heller and Bernd Kasparek, The EU’s Pact against Migration, Part One.

[32] Davies and Isakjee, p. 215

[33] De Genova, Borders of Europe, p. 1 - 35

[34] Ibid, p. 8.

[35] Ibid, p. 1 - 35

[36] New Keywords Collective and Inken Bartels, “We Must Do It Gently”: The Contested Implementation of the IOM’s Migration Management in Morocco,” Migration Studies 5, no. 3 (2017): 315–36, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnx054.

[37] Jeff Crisp, “A New Asylum Paradigm? Globalisation, Migration and the Uncertain Future of the International Refugee Regime,” UN High Commissioner for Refugees 1, no. 1, December 15, 2003, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ff2abf92.html.

[38] De Genova, The Borders of Europe.

[39] Hein de Haas, “The Myth of Invasion: The Inconvenient Realities of African Migration to Europe,” Third World Quarterly 29, no. 7, (2008): 1305 – 1322.

[40] Anna Santos Rasmussen, “When Sovereignty and Solidarity Collide The European Migration-Security Nexus (Dissertation),” New Keywords Collective (2018). https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8956758&fileOId=8956759.

[41] Lizz Schuster, “The Realities of a New Asylum Paradigm,” Oxford, UK: University of Oxford, Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), 2005, https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/2589/.; Jeff Crisp, “A New Asylum Paradigm? Globalisation, Migration and the Uncertain Future of the International Refugee Regime,” UN High Commissioner for Refugees 1, no. 1, December 15, 2003, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ff2abf92.html.

[42] Cantat et al, Migration as crisis.

[43] Heller and Kasparek, The EU’s Pact against Migration, Part One.

[44] Cantat et al, Migration as crisis.

[45] New Keywords Collective, p. 8.

[46] Mayblin, Asylum after Empire.

[47] Delputte and Orbie, Paradigm Shift or Reinventing the Wheel?: Towards a Research Agenda on Change and Continuity in EU Development.

[48] De Genova, Nicolas. The Borders of “Europe”; Mayblin, Asylum after Empire; Kalir, Departheid; Mayblin et al, Necropolitics and the Slow Violence of the Everyday: Asylum Seeker Welfare in the Postcolonial Present.

[49] Hall 1993, p. 279 quoted in Delputte and Orbie 2020, p. 237

[50] Schmidt 2011 in Delputte and Orbie 2020, p. 237

[51] Etienne Bassot and Ariane Debyser, “Setting EU Priorities, 2014-19 The Ten Points of Jean-Claude Juncker’s Political Guidelines,” European Parliamentary Research Service, (2014), p. 10.

[52] Ursula von der Leyen, “A Union That Strives for More: My Agenda for Europe,” 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/political-guidelines-next-commission_en_0.pdf, p. 19.

[53] Heller and Kasparek, The EU’s Pact against Migration, Part One.

[54] European Commission, “Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1366 of 23 September 2020 on an EU Mechanism for Preparedness and Management of Crises Related to Migration,” September 23, 2020, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020H1366.

[55] European Commission, “Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on Asylum and Migration Management and Amending Council Directive (EC) 2003/109 and the Proposed Regulation (EU) XXX/XXX [Asylum and Migration Fund],” September 23, 2020, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0610.

[56] European Commission, “A Fresh Start on Migration: Building Confidence and Striking a New Balance between Responsibility and Solidarity (Press Release),” September 23, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1706.

[57] European Commission, “Amended Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the Establishment of ‘Eurodac’ for the Comparison of Biometric Data for the Effective Application of Regulation (EU) XXX/XXX [Regulation on Asylum and Migration Management] and of Regulation (EU) XXX/XXX [Resettlement Regulation], for Identifying an Illegally Staying Third-Country National or Stateless Person and on Requests for the Comparison with Eurodac Data by Member States’ Law Enforcement Authorities and Europol for Law Enforcement Purposes and Amending Regulations (EU) 2018/1240 and (EU) 2019/818,” September 23, 2020, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0614.

[58] Minos Mouzourakis, More laws, less law, 2020.

[59] De Genova, The borders of Europe.

[60] European Commission, “Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1365 of 23 September 2020 on Cooperation among Member States Concerning Operations Carried out by Vessels Owned or Operated by Private Entities for the Purpose of Search and Rescue Activities,” September 23, 2020, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020H1365.

[61] European Commission, Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1366 of 23 September 2020 on an EU Mechanism for Preparedness and Management of Crises Related to Migration

[62] Ibid, p. 2.

[63] Cantat et al, Migration as crisis.

[64] Minos Mouzourakis, 'More laws, less law', 2020

[65] European Commission, “COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS on the Report on Migration and Asylum,” September 23, 2020, p. 18, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/report-migration-asylum.pdf.

[66] New Keywords Collective, 2016.

[67] Majcher, The EU Return System under the Pact on Migration and Asylum: A Case of Tipped Interinstitutional Balance?

[68] European Commission, Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1364 of 23 September 2020 on Legal Pathways to Protection in the EU: Promoting Resettlement, Humanitarian Admission and Other Complementary Pathways, September 23, 2020, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020H1364.

[69] Meltem Ineli Ciger, “5 Reasons Why: Understanding the Reasons behind the Activation of the Temporary Protection Directive in 2022,” EUmigrationlawblog (blog), March 7, 2022, https://eumigrationlawblog.eu/5-reasons-why-understanding-the-reasons-behind-the-activation-of-the-temporary- protection-directive-in-2022/.

[70] Cantat et al, Migration as crisis; Lavanex and Kunz, 2008.

[71] European Council, “European Council, 24-25 June 2021,” 24 June 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/european-council/2021/06/24-25/.